For Mia and her husband, Leo, their living room wasn’t just a living room; it was a sanctuary carved out of wood and paper. The centerpiece was a massive, bespoke bookshelf, soaring nine feet high, filled not with decorative clutter, but with generations of dense, well-read literature. It backed onto a wall adjoining a lush, overgrown yard, and its heavy pine scent usually masked the subtle smells of the outside world.

Lately, though, something felt off.

It started with tiny details. A biography on the middle shelf, one Mia knew was flush against the wall, was suddenly tilted outward. The corner of a dust jacket on a collection of Victorian poetry seemed inexplicably frayed. Leo swore he saw a thin, gray streak of fur clinging to the edge of a leather-bound dictionary. They blamed the old house settling, or perhaps the family cat, Apollo, having a very ambitious climbing session.

Then came the rustling. It was faint, papery, and always occurred just after they settled down for the night, a sound that suggested tiny, velvet feet dancing on dry leaves—or, in this case, on the brittle pages of forgotten texts. Leo suggested mice. Mia, a meticulous archivist of her own library, felt the mystery ran deeper. A mouse wouldn’t displace a heavy copy of Moby Dick.

One rainy Tuesday afternoon, Mia decided to investigate properly. She was searching for a specific volume on ornithology, a book she knew resided high on the fourth shelf, nestled between a set of heavy reference guides. She pulled a step ladder over, dusted off the rungs, and climbed.

As she reached the shelf, her hand paused. The row of books was tight, solid, and yet… there was a small, furry texture protruding from the gap between Birds of the Northeast and A History of Medieval Architecture. It wasn’t a book tassel. It wasn’t Apollo’s tail.

Mia slowly lowered her face level with the shelf.

She was instantly, utterly lost for words.

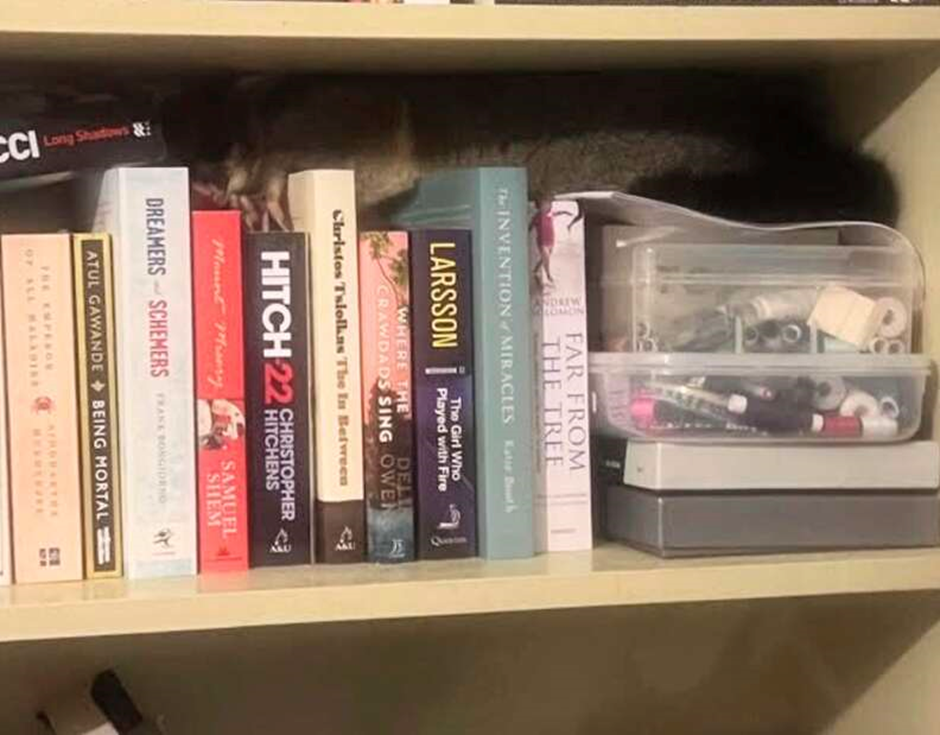

Tucked perfectly, almost insolently, between the thick spines of two ancient, respectable tomes was a tiny, wide-eyed marsupial. It was a baby possum, small enough to fit in the palm of her hand, yet it occupied its lofty perch with the serene confidence of a seasoned reader.

The sight was absurd. Here was this little, pink-nosed creature, a miniature embodiment of the wild, treating their most sacred literary space as its own personal, plush hammock. Its fur was soft gray, and its tiny hands were gripping the edges of the book spines for stability. It wasn’t frightened, only intensely curious.

Mia’s shock gave way to a fit of silent, delighted laughter. It wasn’t a pest; it was a guest. A very cheeky, very well-camouflaged guest. The little creature peered out at her, its dark, glossy eyes reflecting the light from the hallway, its delicate whiskers twitching. It looked less like a wild animal and more like a tiny, gray gremlin who had just finished reviewing the index of the architecture book and was preparing a scathing critique.

She carefully descended the ladder and retrieved her phone to capture the moment of surreal domestic invasion. The first photograph she took perfectly captured the possum nestled securely in its book nook, the spines of the serious, academic works dwarfing its tiny body. It was an image that spoke volumes about the unexpected ways nature can quietly infiltrate human life.

Leo came home an hour later and found Mia sitting quietly in the living room, simply staring up at the bookshelf with a peculiar, soft smile.

“What is it?” he asked, following her gaze. “Did you find the ornithology book?”

Mia simply pointed, and Leo, upon spotting the furry, improbable little face, stopped dead. “Is that… reading?” he whispered.

The possum, seemingly unfazed by the commotion, actually shifted slightly, securing a better grip on a volume of collected short stories, as if adjusting its position for a better read. The second photograph, taken later that evening, showed the possum gripping the spine of a book with its tiny, almost human-like fingers, its expression one of utter contentment—this was its new home, and it was perfect.

The process of getting their tiny librarian down was gentle and slow. They decided against involving rescue services, believing the cub was likely just lost from a nearby den and simply needed to be directed back toward the garden. Using a long, sturdy kitchen spoon, Mia nudged a trail of sliced apple from the shelf, down the wall, and toward a cardboard box placed near the open patio door.

The possum, a surprisingly intellectual eater, ignored the first few pieces of apple, preferring the quiet dignity of its literary lair. Finally, lured by the promise of sugary fruit and the growing darkness outside, it made its move. It scurried down the wall, a swift, gray blur, and vanished into the box.

They carried the box to the dense thicket at the edge of their garden, tipping it gently on its side. The little possum scurried out and immediately disappeared into the protective cover of the ferns, returning to its own wild library.

The next morning, the house felt quieter. The bookshelf, though neatly tidied and dusted, held a new, intangible history. Mia now checks the space between Birds of the Northeast and Medieval Architecture every time she passes, half-expecting, half-hoping to see a pair of curious eyes peering out again. The bookshelf was still a sanctuary, but now, it was also a memorial to the cheekiest, most accidental houseguest they had ever hosted—the little marsupial who had briefly claimed a place among the classics.