Cats are famous for their independence. They love affection on their own terms, but when it comes to roaming, they expect full freedom. Any cat owner knows the routine — the scratching at the door, the meowing demands, and the insistence on being let outside only to return minutes later. Modern pet owners often install a cat flap to avoid being their pet’s personal doorman.

But what many don’t realize is that this isn’t a modern convenience at all. One of the earliest known pet doors was created over four centuries ago at Exeter Cathedral in Devon, England. Amazingly, the opening still exists today, and it remains a passageway for the cathedral’s cats.

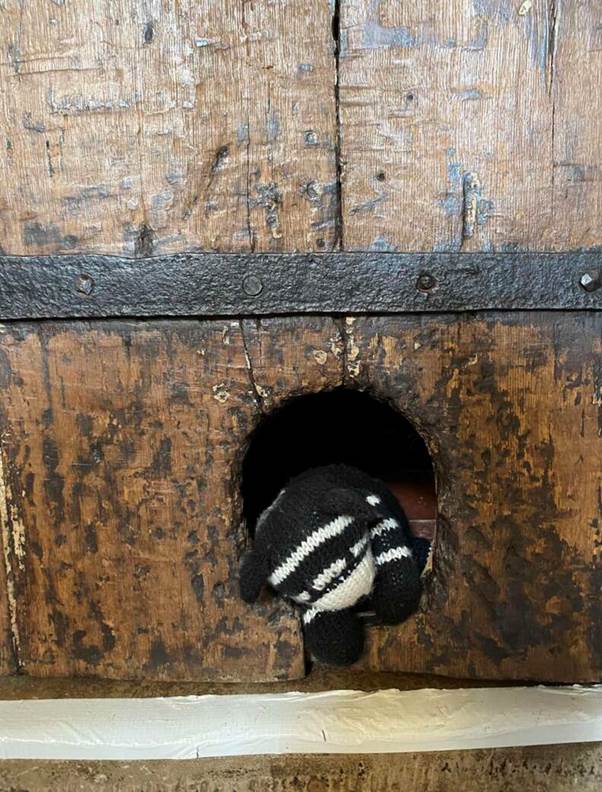

The door is carved into the massive wooden entrance leading to the cathedral’s famous astronomical clock — a stunning piece of craftsmanship that dates back to the late 15th century. For generations, the little hole in the door has allowed feline guardians to slip inside and do their important work.

A Bishop With Foresight

The story begins in 1598, when Bishop William Cotton requested that carpenters cut a round, cat-sized hole into the clock room door. His reasoning was practical. The clock was powered by heavy weights and gears, all of which needed regular maintenance. Workers lubricated the mechanism with animal fat, which unfortunately attracted a steady stream of mice and rats.

A rodent infestation inside the clock tower could have been disastrous — not only chewing through wooden components but also disrupting one of the cathedral’s most treasured features. To prevent this, Bishop Cotton turned to nature’s best exterminator: the domestic cat.

The solution was ingenious. By providing the bishop’s cat with unrestricted access to the clock room, the rodent problem could be controlled without constant human supervision. And so, the hole was cut — a design that would survive the centuries.

This bit of medieval ingenuity even adds a playful layer to the old nursery rhyme:

“Hickory, Dickory, Dock, the mouse ran up the clock.”

As historian Diane Walker notes, the rhyme suddenly makes more sense when viewed in the context of the Exeter clock. The bishop’s cat was there specifically to ensure mice didn’t run up the clock at all.

Cats With Salaries

If carving a private entrance wasn’t enough to show how much cats were valued at Exeter Cathedral, financial records reveal something even more remarkable: the cathedral cats were paid for their work.

Documents from the 14th and 15th centuries record quarterly payments of 13 pence for the care of a cat, with occasional entries of 26 pence. Whether this meant double rations for an especially diligent mouser or the presence of two feline employees is still debated by historians.

This practice of giving cats official “wages” highlights how deeply integrated they were in medieval life. Cats weren’t merely pets; they were essential workers. In an era when food supplies had to be carefully guarded from vermin, cats provided a vital service. Their presence in a cathedral — a place of both religious devotion and community gathering — shows that they were trusted and respected members of daily operations.

It’s fascinating to think of cathedral staff, centuries ago, budgeting funds for the upkeep of a cat just as they would for candles, tools, or food. In many ways, these feline guardians had more job security than some humans of their era.

From Past to Present

Though times have changed, the cat door at Exeter Cathedral is still in use today. The cathedral’s current resident cat, Audrey, proudly carries on the tradition, slipping through the same opening carved more than four centuries ago. Visitors often spot her wandering near the clock, continuing the work of her predecessors.

The only difference? Today’s cathedral cats are no longer on the payroll. Their “payment” comes in the form of warm beds, kind caretakers, and the admiration of visitors who delight in seeing history alive in such a tangible way.

For modern animal lovers, the survival of this cat flap is more than just a quirky architectural detail. It’s a window into a world where humans and animals lived in close partnership, solving everyday problems together. It’s also a reminder that while centuries may pass, the relationship between cats and people has remained remarkably consistent. Cats still guard homes, barns, and — in this case — even churches.

And so, in the heart of a grand cathedral, a simple hole in a wooden door tells a story of practicality, partnership, and affection. Four hundred years later, it remains a symbol of just how far people will go to accommodate the independent spirit of their feline companions.